Barry Ritholtz wrote an opinion piece on Bloomberg today arguing that it's hard to criticize the Fed's QE programs simply because we don't know what would have happened without them. Since this is not a "controlled" experiment in which we can compare a patient taking experimental medication with the one taking a placebo, there is no way to tell if the therapy had worked. All we know is that the patient has undergone a slow recovery and according to the "doctor" may have been worse off without the "treatment".

"If you are testing a new medication to reduce tumors, you want to see what happened to the group that didn't get the test therapy. Maybe this control group experienced rapid tumor growth. Hence, a result where there is no increase in tumor mass in the group receiving the therapy would be considered a very positive outcome."This argument was used a number of times in recent years, including for example with the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 - the $840 billion "stimulus" bill. There are all sorts of estimates on how many jobs the bill saved/created and how many GDP points were added. Was it effective relative to other job creation programs? We of course will never know because we can't peer into an "alternative universe" where the stimulus bill had not passed.

But maybe we are asking the wrong question. Let's for a moment stay with the medication analogy that Mr. Ritholtz introduced. Experimental medication is usually applied in dire cases when the patient's health is deteriorating and traditional therapies had not worked. The use of the first round of quantitative easing, QE1, was just such a case. It was necessary to stabilize the banking system that was frozen - an extreme problem that called for radical measures. But what about QE3? Mr. Ritholtz argues that with other parts of the federal government dysfunctional, the Fed was simply the only game in town to get the economy moving.

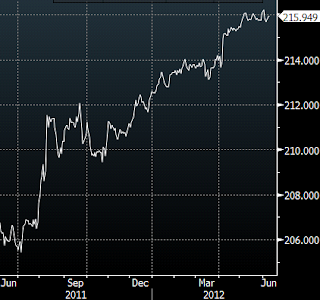

However was the US economy in such a disastrous shape in the summer of 2012 that it called for another extreme intervention? Clearly growth was uneven and the labor markets remained wobbly. Nevertheless a recovery was taking place. A patient who is getting better, albeit slowly, is generally not given an ever larger dose of experimental medication in hopes of miraculously accelerating the recovery.

Rather than Mr. Ritholtz's tumor analogy, let's think about QE as delivering excessive doses of experimental pain killers. Yes the patient may feel better at first, but as we all know, prolonged use could create some nasty side effects. The key side effect of course is addiction - which over a long period of time requires one to administer ever larger doses in order to obtain the same effect. And now you are not just fighting the disorder but also the withdrawal symptoms. That is precisely what is taking place these days (see post). Furthermore, the uncertainty surrounding the QE "withdrawal symptoms" is what had put some of the economic activity on hold, activity that is only now beginning to return (see post).

What's particularly troubling about QE is that even after the "injections" are taken away, the nation's banking system is saddled with the "long-term side effect". The US monetary base is now near $4 trillion, with some $2.5 trillion of it sitting on banks' balance sheets in the form of excess reserves - a situation with no precedent. Removing it would require the Fed to sell its securities holdings - something the central bank is not planning to do. This bloated monetary base is going to be with us for a while even as the Fed's securities purchases end - an "experimental drug" whose long-term effects remain unknown.

SoberLook.comFrom our sponsor: